One of New Mexico’s calling cards, apart from green chile and hot air balloons, is it’s diversity. It is one of only 4 states with a non-hispanic, white population of less than 50%. Unfortunately, the history of the African-Americans in our state is largely untold.

New Mexico has rich African-American history and culture beginning with the arrival of Spanish explorers, continuing with the Homestead Act, through the Civil Rights era, and into the present day where Juneteenth is celebrated across the state.

Juneteenth, for many who do not know, is the oldest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States. The celebration dates back to June 19, 1865, when Union soldiers, led by Major General Gordon Granger, arrived in Galveston, Texas, with news that the war was ended, freeing the enslaved.

This was two and a half years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation; which had become official January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation had little impact on the Texans, or much of the South really, due to the minimal number of Union troops to enforce the new Executive Order.

It wasn’t until the war ended that the enslaved were impacted by the freedom allowed more than 2 years prior in other states. With the surrender of General Lee in April of 1865, and the arrival of General Granger’s regiment, forces were finally strong enough to influence and overcome resistance from the people in the southern states.

It wasn’t until 2006 that legislation was passed making New Mexico the 19th state to recognize Juneteenth as a holiday. With the passage of House Bill 228 sponsored by Majority Whip Sheryl Williams Stapleton and supported by many legislators, “Juneteenth Freedom Day” was honored, and we celebrate it in cities all around the state.

Juneteenth today, celebrates African- American freedom and achievement, while encouraging continuous self-development and respect for all cultures. As it takes on a more national, symbolic and even global perspective, the events of 1865 in Texas are not forgotten.

The history of African-Americans in New Mexico dates back to when the state was still a territory, but little is taught or discussed about this history.

The first African-American community in NM, when it was still a territory, and a black woman who made herself resemble a man to serve in the military in the 1800s are little-known stories that are as much a part of the state’s fabric as its pueblos, Spanish Conquistadors, Route 66 and nuclear experiments are.

We should know and appreciate these stories, because they helped shape the state into what we know it as today.

Cathay Williams

Cathay Williams was a black woman in New Mexico who made herself resemble a man to serve in the military in the 1800s. She enlisted in the US Army under the pseudonym ‘William Cathay’ in 1866.

She was the first African-American woman to enlist, and the only one documented to to serve in the US Army as a man.

Shortly after her enlistment, she contracted smallpox and was hospitalized. Williams was able to rejoin her unit in New Mexico after recovering.

There, possibly due to the effects of smallpox, the heat, or the years of marching, her body began to show signs of strain.

Due to her frequent hospitalization thereafter, the Army Post Surgeon finally discovered she was a woman and informed the post commander. She was honorably discharged by her commanding officer, Captain Charles E. Clarke on October 14, 1868 after serving for 2 years.

Though her disability discharge meant the end of her tenure with the Army, her advenure continued.

She signed up with an emerging all-black regiment that would eventually become part of the legendary Buffalo Soldiers.

Blackdom

Blackdom was a small town near Roswell that was the first African-American community in the New Mexico Territory. It was a freedom colony that was founded in 1901 when an African-American teacher and his wife, Frank & Ella Boyer, relocated from Georgia to escape the threats of the Ku Klux Klan. The establishment of the homestead was to seek safety for themselves and others.

The first homesteaders then started advertising in local papers to encourage others to join their homestead.

By 1908, the community had 25 families with about 300 people and a number of businesses (including a blacksmith shop, a hotel, a weekly newspaper, and a Baptist church) on 15,000 acres of land.

W.T. Malone, the first African-American to pass the New Mexico Bar exam, was one of the early settlers from Mississippi.

The community was the first solely African-American community in the New Mexico Territory.

The community thrived for years, however 1916 saw worms infest much of the crops, alkali buildup in the soil, and the sudden depletion of the natural wells of the Artesia aquifer that had provided most of the water for the farms. Sadly, this forced settlers to began leaving the area.

In 1921, the house of the Boyer’s was foreclosed upon and the family relocated, much like many other settlers had done prior.

Blackdom was officially incorporated that same year. However, by the time it was recognized as a town, most of the population had relocated because of the water problems.

There are no structures remaining in Blackdom, with the exception of the barely visible concrete foundation of the school-house.

However, The Blackdom Baptist Church building was sold in the 1920s and moved to the town of Cottonwood in Eddy County, where it is now a private home.

Buffalo Soldiers

At the end of the Civil War, Black cavalry and infantry troops known as buffalo soldiers were sent to the American west to take part in the Indian wars and the protection of settlers.

The term “buffalo soldier” is said to have been applied to the Black troops by the Indians because of their short curly hair and their courage and fortitude, much admired qualities of the buffalo. The term was first applied to Black soldiers of the 10th Cavalry Regiment in 1866 by the Kiowa Indians in western Kansas after encounters with them.

It was taken as a compliment by the troops and the 10th Cavalry adopted a picture of the buffalo as its regiment’s crest.

In 1866, 8 black infantries marched to New Mexico, where they began to help keep peace in the area, and maintain order. These first buffalo soldiers to be stationed in frontier New Mexico also had many more menial responsibilities.

They (as well as White soldiers) were responsible, in some cases for major construction and renovations at the forts where they were stationed and served as carpenters, plasterers, painters, and bricklayers. The Black soldiers were also responsible for other menial work, such as fuel gathering, always a difficult task in the sparse desert environment of southern New Mexico.

Men would have to go as far as fifteen miles from the fort to find adequate wood supplies and often had to laboriously dig up mesquite roots for fuel.

By the early 1870s, due to complaints by officers in New Mexico, the Army began to contract for many laboring jobs and for supplies such as fuel, hay, and building supplies, thus freeing the Black soldiers from many of these onerous tasks.

They then served in maintaining order during the Colfax County War and the Lincoln County War, facing the outlaws of the Wild West, including the famous, Billy the Kid.

Their presence in the state was prominent in the late 1800s where many of these soldiers worked closely with law enforcement to keep the peace between outlaws.

Among their final duties in New Mexico was the closing and dismantling of Fort Selden in 1891 and Fort Stanton in 1896, an indication of the peaceable conditions now reigning in the territory.

Here ended the role of the buffalo soldiers in New Mexico in the Indian Wars of the nineteenth century.

The history of the African-Americans in New Mexico was richly beneficial to the area becoming a state, and the Wild West remaining in order. It is just another attribute of New Mexico, and adds to the diversity we are proud of.

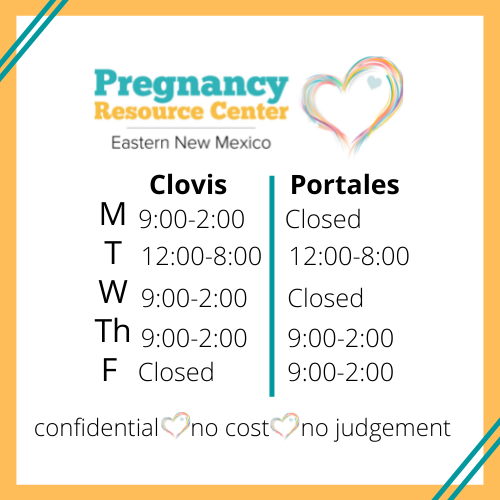

Juneteenth is a date to celebrate all that rich history. There are events in both Clovis and Portales, among cities across the nation each year, in honor of the day that changed it all.